Back in April 2024, Jason Zimdars from 37signals published a post about modern CSS patterns in Campfire. He explained how their team builds sophisticated web applications using nothing but vanilla CSS. No Sass. No PostCSS. No build tools.

The post stuck with me. Over the past year and a half, 37signals has released two more products (Writebook and Fizzy) built on the same nobuild philosophy. I wanted to know if these patterns held up. Had they evolved?

I cracked open the source code for Campfire, Writebook, and Fizzy and traced the evolution of their CSS architecture. What started as curiosity became genuine surprise. These are not just consistent patterns. They are improving patterns. Each release builds on the last, adopting progressively more modern CSS features while maintaining the same nobuild philosophy.

These are not hobby projects. Campfire is a real-time chat application. Writebook is a publishing platform. Fizzy is a full-featured project management tool with kanban boards, drag-and-drop, and complex state management. Combined, they represent nearly 14,000 lines of CSS across 105 files.

Not a single line touches a build tool.

The Tailwind Question

Let me be clear: there is nothing wrong with Tailwind. It is a fantastic tool that helps developers ship products faster. The utility-first approach is pragmatic, especially for teams that struggle with CSS architecture decisions.

But somewhere along the way, utility-first became the only answer. CSS has evolved dramatically. The language that once required preprocessors for variables and nesting now has:

- Native custom properties (variables)

- Native nesting

- Container queries

- The

:has()selector (finally, a parent selector) - CSS Layers for managing specificity

color-mix()for dynamic color manipulationclamp(),min(),max()for responsive sizing without media queries

37signals looked at this landscape and made a bet: modern CSS is powerful enough. No build step required.

Three products later, that bet is paying off.

The Architecture: Embarrassingly Simple

Open any of these three codebases and you find the same flat structure:

app/assets/stylesheets/

├── _reset.css

├── base.css

├── colors.css

├── utilities.css

├── buttons.css

├── inputs.css

├── [component].css

└── ...

That is it. No subdirectories. No partials. No complex import trees. One file per concept, named exactly what it does.

Zero configuration. Zero build time. Zero waiting.

I would love to see something like this ship with new Rails applications. A simple starting structure with _reset.css, base.css, colors.css, and utilities.css already in place. I suspect many developers reach for Tailwind not because they prefer utility classes, but because vanilla CSS offers no starting point. No buckets. No conventions. Maybe CSS needs its own omakase.

The Color System: Consistent Foundation, Evolving Capabilities

Jason’s original post explained OKLCH well. It is the perceptually uniform color space all three apps use. The short version: unlike RGB or HSL, OKLCH’s lightness value actually corresponds to perceived brightness. A 50% lightness blue looks as bright as a 50% lightness yellow.

What is worth noting is how this foundation remains identical across all three apps:

:root {

/* Raw LCH values: Lightness, Chroma, Hue */

--lch-blue: 54% 0.15 255;

--lch-red: 51% 0.2 31;

--lch-green: 65% 0.23 142;

/* Semantic colors built on primitives */

--color-link: oklch(var(--lch-blue));

--color-negative: oklch(var(--lch-red));

--color-positive: oklch(var(--lch-green));

}

Dark mode becomes trivial:

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

:root {

--lch-blue: 72% 0.16 248; /* Lighter, slightly desaturated */

--lch-red: 74% 0.18 29;

--lch-green: 75% 0.20 145;

}

}

Every color that references these primitives automatically updates. No duplication. No separate dark theme file. One media query, and the entire application transforms.

Fizzy takes this further with color-mix():

.card {

--card-color: oklch(var(--lch-blue-dark));

/* Derive an entire color palette from one variable */

--card-bg: color-mix(in srgb, var(--card-color) 4%, var(--color-canvas));

--card-text: color-mix(in srgb, var(--card-color) 30%, var(--color-ink));

--card-border: color-mix(in srgb, var(--card-color) 33%, transparent);

}

One color in, four harmonious colors out. Change the card color via JavaScript (element.style.setProperty('--card-color', '...')), and the entire card theme updates automatically. No class swapping. No style recalculation. Just CSS doing what CSS does best.

The Spacing System: Characters, Not Pixels

Here is a pattern I did not expect: all three applications use ch units for horizontal spacing.

:root {

--inline-space: 1ch; /* Horizontal: one character width */

--block-space: 1rem; /* Vertical: one root em */

}

.component {

padding-inline: var(--inline-space);

margin-block: var(--block-space);

}

Why characters? Because spacing should relate to content. A 1ch gap between words feels natural because it is literally the width of a character. As font size scales, spacing scales proportionally.

This also makes their responsive breakpoints unexpectedly elegant:

@media (min-width: 100ch) {

/* Desktop: content is wide enough for sidebar */

}

Instead of asking “is this a tablet?”, they are asking “is there room for 100 characters of content?” It is semantic. It is content-driven. It works.

Utility Classes: Yes, They Still Exist

Let me address the elephant in the room. These applications absolutely use utility classes:

/* From utilities.css */

.flex { display: flex; }

.gap { gap: var(--inline-space); }

.pad { padding: var(--block-space) var(--inline-space); }

.txt-large { font-size: var(--text-large); }

.hide { display: none; }

The difference? These utilities are additive, not foundational. The core styling lives in semantic component classes. Utilities handle the exceptions: the one-off layout adjustment, the conditional visibility toggle.

Compare to a typical Tailwind component:

<!-- Tailwind approach -->

<button class="inline-flex items-center gap-2 px-4 py-2 rounded-full

border border-gray-300 bg-white text-gray-900

hover:bg-gray-50 focus:ring-2 focus:ring-blue-500">

Save

</button>

And the 37signals equivalent:

<!-- Semantic approach -->

<button class="btn">Save</button>

.btn {

--btn-padding: 0.5em 1.1em;

--btn-border-radius: 2em;

display: inline-flex;

align-items: center;

gap: 0.5em;

padding: var(--btn-padding);

border-radius: var(--btn-border-radius);

border: 1px solid var(--color-border);

background: var(--btn-background, var(--color-canvas));

color: var(--btn-color, var(--color-ink));

transition: filter 100ms ease;

}

.btn:hover {

filter: brightness(0.95);

}

.btn--negative {

--btn-background: var(--color-negative);

--btn-color: white;

}

Yes, it is more CSS. But consider what you gain:

- HTML stays readable.

class="btn btn--negative"tells you what something is, not how it looks. - Changes cascade. Update

--btn-paddingonce, every button updates. - Variants compose. Add

.btn--circlewithout redefining every property. - Media queries live with components. Dark mode, hover states, and responsive behavior are co-located with the component they affect.

The :has() Revolution

If there is one CSS feature that changes everything, it is :has(). For decades, you needed JavaScript to style parents based on children. No more.

Writebook uses it for a sidebar toggle with no JavaScript:

/* When the hidden checkbox is checked, show the sidebar */

:has(#sidebar-toggle:checked) #sidebar {

margin-inline-start: 0;

}

Fizzy uses it for kanban column layouts:

.card-columns {

grid-template-columns: 1fr var(--column-width) 1fr;

}

/* When any column is expanded, adjust the grid */

.card-columns:has(.cards:not(.is-collapsed)) {

grid-template-columns: auto var(--column-width) auto;

}

Campfire uses it for intelligent button styling:

/* Circle buttons when containing only icon + screen reader text */

.btn:where(:has(.for-screen-reader):has(img)) {

--btn-border-radius: 50%;

aspect-ratio: 1;

}

/* Highlight when internal checkbox is checked */

.btn:has(input:checked) {

--btn-background: var(--color-ink);

--btn-color: var(--color-ink-reversed);

}

This is CSS doing what you used to need JavaScript for. State management. Conditional rendering. Parent selection. All declarative. All in stylesheets.

Progression

What fascinated me most was watching the architecture evolve across releases.

Campfire (first release) established the foundation:

- OKLCH colors

- Custom properties for everything

- Character-based spacing

- Flat file organization

- View Transitions API for smooth page changes

Writebook (second release) added modern capabilities:

- Container queries for component-level responsiveness

@starting-stylefor entrance animations

Fizzy (third release) went all-in on modern CSS:

- CSS Layers (

@layer) for managing specificity color-mix()for dynamic color derivation- Complex

:has()chains replacing JavaScript state

You can see a team learning, experimenting, and shipping progressively more sophisticated CSS with each product. By Fizzy, they are using features many developers do not even know exist.

/* Fizzy's layer architecture */

@layer reset, base, components, modules, utilities;

@layer components {

.btn { /* Always lower specificity than utilities */ }

}

@layer utilities {

.hide { /* Always wins over components */ }

}

CSS Layers solve the specificity wars that have plagued CSS since the beginning. It does not matter what order your files load. It does not matter how many classes you chain. Layers determine the winner, period.

The Loading Spinner

One technique appears in all three applications that deserves special attention. Their loading spinners use no images, no SVGs, no JavaScript. Just CSS masks.

Here is the actual implementation from Fizzy’s spinners.css:

@layer components {

.spinner {

position: relative;

&::before {

--mask: no-repeat radial-gradient(#000 68%, #0000 71%);

--dot-size: 1.25em;

-webkit-mask: var(--mask), var(--mask), var(--mask);

-webkit-mask-size: 28% 45%;

animation: submitting 1.3s infinite linear;

aspect-ratio: 8/5;

background: currentColor;

content: "";

inline-size: var(--dot-size);

inset: 50% 0.25em;

margin-block: calc((var(--dot-size) / 3) * -1);

margin-inline: calc((var(--dot-size) / 2) * -1);

position: absolute;

}

}

}

The keyframes live in a separate animation.css file:

@keyframes submitting {

0% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 0%, 50% 0%, 100% 0% }

12.5% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 50%, 50% 0%, 100% 0% }

25% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 100%, 50% 50%, 100% 0% }

37.5% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 100%, 50% 100%, 100% 50% }

50% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 100%, 50% 100%, 100% 100% }

62.5% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 50%, 50% 100%, 100% 100% }

75% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 0%, 50% 50%, 100% 100% }

87.5% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 0%, 50% 0%, 100% 50% }

100% { -webkit-mask-position: 0% 0%, 50% 0%, 100% 0% }

}

Three dots, bouncing in sequence:

The background: currentColor means it automatically inherits the text color. Works in any context, any theme, any color scheme. Zero additional assets. Pure CSS creativity.

A Better <mark>

The default browser <mark> element renders as a yellow highlighter. It works, but it is not particularly elegant. Fizzy takes a different approach for search result highlighting: drawing a hand-drawn circle around matched terms.

Here is the implementation from circled-text.css:

@layer components {

.circled-text {

--circled-color: oklch(var(--lch-blue-dark));

--circled-padding: -0.5ch;

background: none;

color: var(--circled-color);

position: relative;

white-space: nowrap;

span {

opacity: 0.5;

mix-blend-mode: multiply;

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

mix-blend-mode: screen;

}

}

span::before,

span::after {

border: 2px solid var(--circled-color);

content: "";

inset: var(--circled-padding);

position: absolute;

}

span::before {

border-inline-end: none;

border-radius: 100% 0 0 75% / 50% 0 0 50%;

inset-block-start: calc(var(--circled-padding) / 2);

inset-inline-end: 50%;

}

span::after {

border-inline-start: none;

border-radius: 0 100% 75% 0 / 0 50% 50% 0;

inset-inline-start: 30%;

}

}

}

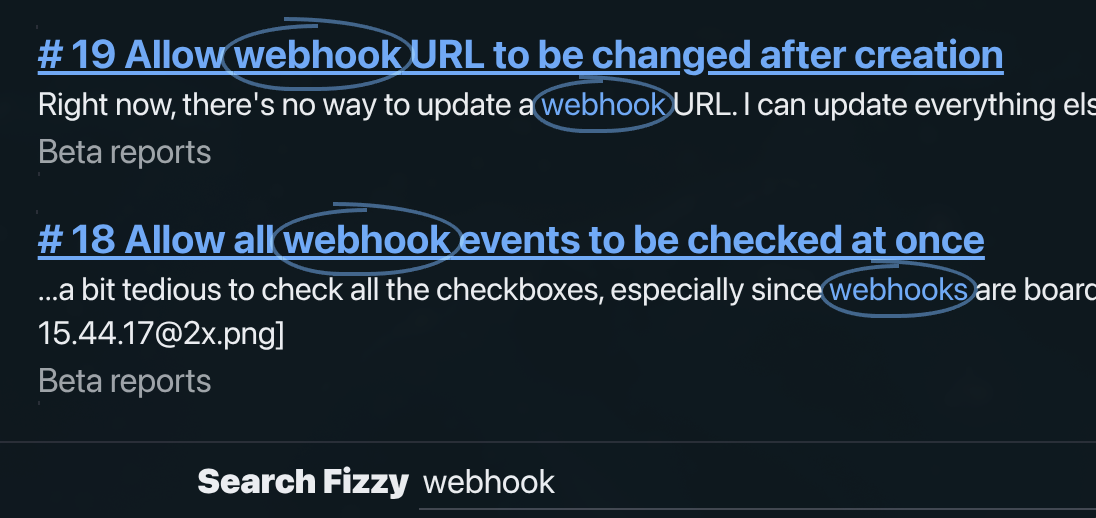

The HTML structure is <mark class="circled-text"><span></span>webhook</mark>. The empty span exists solely to provide two pseudo-elements (::before and ::after) that draw the left and right halves of the circle.

The technique uses asymmetric border-radius values to create an organic, hand-drawn appearance. The mix-blend-mode: multiply makes the circle semi-transparent against the background, switching to screen in dark mode for proper blending.

Search results for: webhook

No images. No SVGs. Just borders and border-radius creating the illusion of a hand-drawn circle.

Dialog Animations: The New Way

Fizzy and Writebook both animate HTML <dialog> elements. This was notoriously difficult before. The secret is @starting-style.

Here is the actual implementation from Fizzy’s dialog.css:

@layer components {

:is(.dialog) {

border: 0;

opacity: 0;

transform: scale(0.2);

transform-origin: top center;

transition: var(--dialog-duration) allow-discrete;

transition-property: display, opacity, overlay, transform;

&::backdrop {

background-color: var(--color-black);

opacity: 0;

transform: scale(1);

transition: var(--dialog-duration) allow-discrete;

transition-property: display, opacity, overlay;

}

&[open] {

opacity: 1;

transform: scale(1);

&::backdrop {

opacity: 0.5;

}

}

@starting-style {

&[open] {

opacity: 0;

transform: scale(0.2);

}

&[open]::backdrop {

opacity: 0;

}

}

}

}

The --dialog-duration variable is defined globally as 150ms.

The @starting-style rule defines where the animation starts from when an element appears. Combined with allow-discrete, you can now transition between display: none and display: block. The modal smoothly scales and fades in. The backdrop fades independently. No JavaScript animation libraries. No manually toggling classes. The browser handles it.

What This Means for You

I am not suggesting you abandon your build tools tomorrow. But I am suggesting you reconsider your assumptions.

You might not need Sass or PostCSS. Native CSS has variables, nesting, and color-mix(). The features that needed polyfills are now baseline across browsers.

You might not need Tailwind for every project. Especially if your team understands CSS well enough to build a small design system.

While the industry sprints toward increasingly complex toolchains, 37signals is walking calmly in the other direction. Is this approach right for everyone? No. Large teams with varying CSS skill levels might benefit from Tailwind’s guardrails. But for many projects, their approach is a reminder that simpler can be better.

Thanks to Jason Zimdars and the 37signals team for sharing their approach openly. All code examples in this post are taken from the Campfire, Writebook, and Fizzy source code. For Jason’s original deep-dive into Campfire’s CSS patterns, see Modern CSS Patterns and Techniques in Campfire. If you want to learn modern CSS, these three codebases are an exceptional classroom.